Torts notes

Reading comprehension

Reading and math skills

Some procedure

Burdens of proof

In Black's Law Dictionary, look up:

- Burden of proof

- Burden of pleading

- Burden of production

- Burden of persuasion

Standards of proof

Black's Law Dictionary defines "standard of proof" as "[t]he degree or level of proof demanded in a specific case, such as 'beyond a reasonable doubt' or 'by a preponderance of the evidence'; a rule about the quality of the evidence that a party must bring forward to prevail."

Preponderance of the evidence standard

In most (but not all) contexts, the standard of proof in a tort action is "a preponderance of the evidence." In an 1895 case, the South Carolina Supreme Court approved of the following jury instructions given by the circuit court judge to the jury in a civil case:

I charge you that should you not be satisfied by the preponderance of the evidence that the defense of the defendant is sustained, then you will have to consider the case as made out by the plaintiff; and then upon him will fall the burden of proof to make out his case by the same standard, the preponderance of the evidence. By that is meant, Mr. Foreman and gentlemen, the greater weight of the testimony on the issues involved. No court can provide a jury with scales on which to weigh the evidence; but a jury of twelve intelligent men, who have a knowledge of human nature, and, from their observation of life, understand the rules of common sense, are in possession of the best scales on which to weigh evidence. When a jury comes to the conclusion that a defendant has brought forward evidence that satisfies them that, more likely than not, such and such was the case, then they may say he has established his defense by the preponderance of the evidence; or when the plaintiff satisfies the jury by competent evidence that it is more likely than not that such and such was the case, not absolutely proved, not absolutely true, because neither the plaintiff nor the defendant is called upon to establish his complaint or make out his defense beyond a reasonable doubt, but, by the preponderance of the evidence, that it is more likely than not that such and such was the case, then you may safely say that the defense has been made out by the preponderance of the evidence, or that the complaint has been established by the preponderance of the evidence.”

Groesbeck v. Marshall, 44 S.C. 538, 22 S.E. 743 (1895).

This remains an accurate statement of the law today, with one exception.

Juries

A jury in 1895 would most likely have excluded African Americans as well. (South Carolina adopted its infamous Jim Crow constitution that same year.) Unrepresentative juries are still a problem today. For a perspective on juries in criminal cases, see Emily Paavola and Linsey Vann, A Jury of Your Peers? Not Always in South Carolina (2016)

Civil versus criminal

In a criminal case, a government prosecutes a defendant for a criminal act.

In a civil case, a plaintiff sues a defendant for violating a private right.

"Civil"

As you know, civil law is broader than just tort law. And "civil law" also has a different meaning that's especially important in Louisiana, Quebec, and countries outside the former British Commonwealth. If you're interested, it's a great question for office hours!

We'll see similar linguistic issues arise repeatedly during the semester: Seemingly simple words often have multiple meanings that may diverge, overlap, and differ from common understandings. Pay attention to this as you read and write throughout your career.

In fact, you might even consider starting a list now. If you do, here's another important term to add: "holding." We'll discuss it soon.

Evidence

Satisfying the burden of proof requires evidence. Consider these model jury instructions:

Evidence can come in many forms. It can be testimony about what someone saw or heard or smelled. It can be an exhibit admitted into evidence. It can be someone’s opinion.

Direct evidence can prove a fact by itself. For example, if a witness testifies she saw a jet plane flying across the sky, that testimony is direct evidence that a plane flew across the sky.

Some evidence proves a fact indirectly. For example, a witness testifies that he saw only the white trail that jet planes often leave. This indirect evidence is sometimes referred to as 'circumstantial evidence.' In either instance, the witness's testimony is evidence that a jet plane flew across the sky.

As far as the law is concerned, it makes no difference whether evidence is direct or indirect. You may choose to believe or disbelieve either kind. Whether it is direct or indirect, you should give every piece of evidence whatever weight you think it deserves.

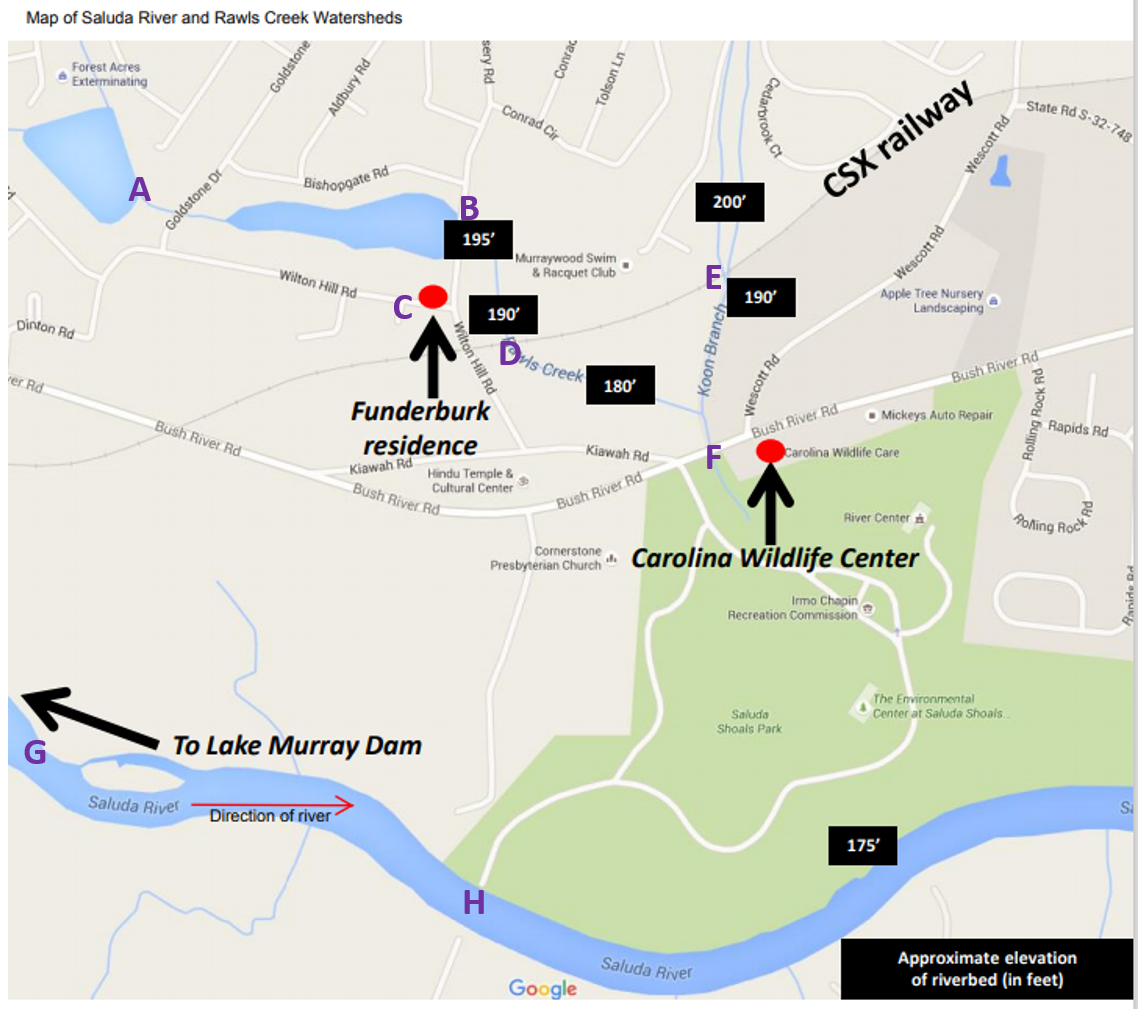

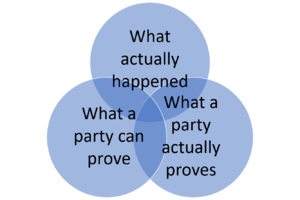

The "facts" in a courtroom can differ from the "facts" on the ground:

Why might this be?

Venn diagrams

We will be using many stylized Venn and Euler Diagrams!

Facts versus law

Other standards

We've already discussed standards of proof. Soon we will also discuss other important standards at the trial and appellate levels. Consider, for example:

- What standard should a trial court apply when deciding whether to grant a motion for summary judgment?

- What standard should an appellate court apply when deciding whether to affirm or reverse a trial court's decision to grant that motion?

Testing your briefing

Except where you are told otherwise, you must answer these questions by referring only to your brief -- not to the case itself.

Levels of culpability

Theories of liability

Elements of negligence

Much of this course focuses on "the five elements of the prima facie case of negligence plus the affirmative defenses." These five elements of the prima facie case of negligence are:

- Duty: Whether tort law imposes a standard of care on this kind of defendant in this kind of case.

- Breach: Whether the defendant's conduct fell below that standard of care.

- Factual Cause: Whether the defendant's breach contributed to the plaintiff's harm.

- Scope of Liability: Whether the defendant should be held liable under the specific circumstances of this particular case.

- Damages: Whether the plaintiff suffered a harm for which tort law provides a remedy.

The plaintiff must prove the prima facie case. This means that the plaintiff has the burden of pleading each element, the burden of producing evidence about each element, and the burden of persuading the judge or jury that this evidence satisfies the standard of proof for each element. (Recall: What is the most common standard of proof in tort law?)

Whereas the element of duty is a question of law that is (mostly) decided by the judge, the remaining elements are questions of fact that are (mostly) decided by the finder of fact. (Recall: Who is the finder of fact in a jury trial? Who is the finder of fact in a bench trial?) We will soon talk more about what "mostly" means.

The defendant can offer evidence and arguments for why the plaintiff's prima facie case should fail. Remember: T he plaintiff has the burden of proof on the prima facie case, which means that the defendant's evidence and arguments can make it more difficult for the plaintiff to carry that burden.

In addition, the defendant can raise one or more " affirmative defenses" that apply even if the plaintiff proves the prima facie case. In contrast to the prima facie case, the defendant must plead and prove an affirmative defense. This is why it is called an "affirmative" defense. In effect, the defendant argues that even if the elements of negligence are satisfied, there is some other reason why the plaintiff should recover either no damages or less than their full damages.

You have already seen an example of this. Stop and think! What was the defendant's argument in Baltimore & O.R. Co. v. Goodman, 275 U.S. 66 (1927)? Stop and think! This affirmative defense was called "contributory negligence": The plaintiff should recover nothing because their own unreasonable conduct was a cause of their harm. Was it successful? Stop and think!

Early in the semester, many students confuse the element of breach in the prima facie case with an affirmative defense such as contributory negligence or (as we will see) comparative fault. Don't make this mistake! The element of breach is about the defendant's conduct, not the plaintiff's! The reasonableness of the plaintiff's conduct might have nothing to do with the reasonableness of the defendant's conduct. (Like most things, we will complicate this slightly over the course of the semester.)

This brings us to another crucial point: Reality is messier than theory.

In our course, you will see how the substance of tort law varies both across time and across space: Different jurisdictions (and even different judges in the same jurisdiction) do different things at different times. Each state has its own common law, and that common law changes both subtly and dramatically over time. Some jurisdictions still follow legal rules that other jurisdictions abandoned half a century ago. And some jurisdictions have even returned to rules that they once abandoned.

You will also see how the language of tort law varies both across time and across space: Different jurisdictions (and even different judges in the same jurisdiction) say the same things in different ways or say different things in the same ways. For example, later this semester we will see how different courts might frame the very same issue as one of duty or of breach or of scope of liability or of assumption of risk (another affirmative defense). This framing can even affect the outcome: Substance and language are in many ways inextricably intertwined.

Consider one final--and very important--example: As you will see in our upcoming cases, many courts still refer to "proximate cause" as one of the elements of negligence. Some use this term to refer only to the element of cause-in-fact, some use it to refer only to the element of scope of liability, and some use it to refer to the combination of these two elements. Because I find this term confusing, I do not use it in our course. Should you? Stop and think!

The answer has little to do with whether this term is actually confusing, whether you find it confusing, or even whether I find it confusing. Rather, the answer has everything to do with an essential legal skill: Knowing your audience. For the purpose of your grade in this course, I am your audience. It is a jurisdiction of one. You should not use this term in this course because I (usually) do not want to hear it in this course.

After you finish this course, however, your audience is unlikely to be (only) me. How will your answer change if, in the future, you are taking a bar exam that still uses the term? If you are working for a lawyer or arguing before a judge who prefers it? If you are talking with a client who doesn't understand it?

That last one is a trick question. Over the next few weeks, you are going to learn a ton of legal substance and legal language. You will probably vomit your new legal vocabulary in ways that, in retrospect, will be hilarious. And then you will get gradually more competent and correspondingly more confident. Keep your competence and confidence aligned! And never forget what it feels like now. Your ability to talk clearly, simply, and relatably with clients, witnesses, and jurors -- often without legal terms of art -- will be one of your greatest strengths as a lawyer.

Whenever you encounter a new term of art, note it, define it, and make sure that you can use it correctly -- but also make sure that you can explain the same concept without it. This is great practice -- with your friends, family, pets, and blank walls. And it's even appeared on at least one of my past exams.

So what are the elements of the prima facie case of negligence?

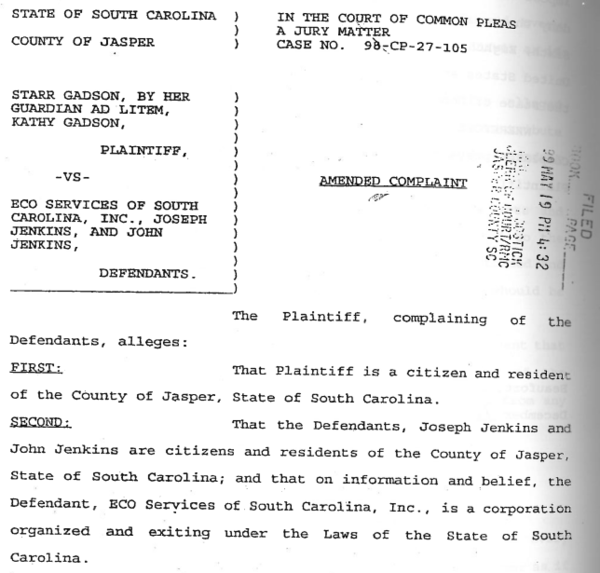

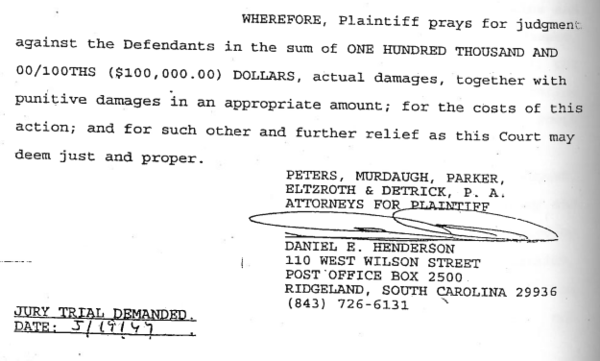

Complaint

You have already read about the "complaint" -- one of the key documents with which a plaintiff starts a lawsuit.

This is the beginning of the complaint in Gadson v. ECO Services:

And this is the end of that complaint:

Your task is to draft the middle of the complaint. It should be clear, concise, organized, and accurate. Two careful pages is likely to suffice.

- The following questions may help you to think through the structure and content of your complaint:

- What are the key facts?

- Who are the defendants? (There are three!)

- What are the claims against each defendant?

- What are the elements of each claim?

- How do the facts relate to each element?

You are welcome to work alone or with others to draft your complaint. Regardless, you must bring your own individual copy.

Model complaint

Do not read this until after class.

Note 1: This is a stylized model for the substantive portions of Starr Gadson's complaint. You will learn about the specific requirements for complaints next semester.

Note 2: It is also acceptable to use the elements of negligent entrustment in addition to or instead of the elements of negligence for claims against ECO and Joseph Jenkins.

Facts

- ECO Services made its truck available to its employee, Joseph Jenkins.

- Joseph allowed John to drive the truck.

- John drove the truck dangerously.

- This dangerous driving resulted in a crash.

- Starr sustained serious physical and emotional injuries because of the crash.

Claim of negligence against John Jenkins

- Duty: John had a duty to exercise reasonable care while driving.

- Breach: John drove dangerously.

- Cause-in-fact: John's dangerous driving caused the crash that injured Starr.

- Scope of liability: It was foreseeable that John's dangerous driving would injure Starr.

- Damages: Starr suffered serious physical and emotional injuries.

Claim[s] of negligence [or negligence and negligent entrustment] against Joe Jenkins

- Duty: Joseph had a duty to exercise reasonable care in loaning the truck.

- Breach: Joseph loaned his truck to a dangerous driver.

- Cause-in-fact: Joseph's decision to loan his truck enabled John's dangerous operation of that truck and, ultimately, the crash that injured Starr.

- Scope of liability: It was foreseeable that loaning a truck to a dangerous driver could result in a serious crash.

- Damages: Starr suffered serious physical and emotional injuries.

Claim[s] of negligence [or negligence and negligent entrustment] against ECO

- Duty: ECO had a duty to exercise reasonable care in making its truck available to its employees.

- Breach: ECO made its truck available to a person, Joseph, who should not have been trusted.

- Cause-in-fact: ECO's decision to make its truck available to Joseph enabled Joseph to loan the truck to John, which enabled John's dangerous operation of that truck and, ultimately, the crash that injured Starr.

- Scope of liability: It was foreseeable that loaning a truck to someone who was not trustworthy could result in a serious crash.

- Damages: Starr suffered serious physical and emotional injuries.