Difference between revisions of "Torts notes"

Neumoeglich (talk | contribs) |

Neumoeglich (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 598: | Line 598: | ||

# How do the facts relate to each element? | # How do the facts relate to each element? | ||

| − | You are welcome to work alone or with others to draft your complaint. Regardless, you must bring your own individual | + | The court discusses ''negligent entrustment'' at length -- and soon we will too. For this exercise, however, I suggest you draft your complaint to allege only a claim of ''negligence'' generally against each of the three defendants (for a total of three claims). |

| + | |||

| + | You are welcome to work alone or with others to draft your complaint. Regardless, you must print and bring your own individual hardcopy. | ||

== Model complaint == | == Model complaint == | ||

Revision as of 07:48, 28 August 2023

Note: Each heading is assigned separately. Check to make sure you are not accidentally doing more work than assigned.

Reading comprehension

(This is the end of one section. The next section corresponds to a future assignment.)

Reading and math skills

Some procedure

This note includes all the subheadings through "Other standards."

Burdens of proof

In Black's Law Dictionary, look up:

- Burden of proof

- Burden of pleading

- Burden of production

- Burden of persuasion

Standards of proof

Black's Law Dictionary defines "standard of proof" as "[t]he degree or level of proof demanded in a specific case, such as 'beyond a reasonable doubt' or 'by a preponderance of the evidence'; a rule about the quality of the evidence that a party must bring forward to prevail."

Preponderance of the evidence standard

In most (but not all) contexts, the standard of proof in a tort action is "a preponderance of the evidence." In an 1895 case, the South Carolina Supreme Court approved of the following jury instructions given by the circuit court judge to the jury in a civil case:

[T]hen you will have to consider the case as made out by the plaintiff; and then upon him will fall the burden of proof to make out his case by the same standard, the preponderance of the evidence. By that is meant, Mr. Foreman and gentlemen, the greater weight of the testimony on the issues involved. No court can provide a jury with scales on which to weigh the evidence; but a jury of twelve intelligent men, who have a knowledge of human nature, and, from their observation of life, understand the rules of common sense, are in possession of the best scales on which to weigh evidence.... [W]hen the plaintiff satisfies the jury by competent evidence that it is more likely than not that such and such was the case, not absolutely proved, not absolutely true, because neither the plaintiff nor the defendant is called upon to establish his complaint or make out his defense beyond a reasonable doubt, but, by the preponderance of the evidence, that it is more likely than not that such and such was the case, then you may safely say ... that the complaint has been established by the preponderance of the evidence.”

Groesbeck v. Marshall, 44 S.C. 538, 22 S.E. 743 (1895).

This remains an accurate statement of the law today, with one exception.

Juries

A jury in 1895 would most likely have excluded African Americans as well. (South Carolina adopted its infamous Jim Crow constitution that same year.) Unrepresentative juries are still a problem today. For a perspective on juries in criminal cases, see Emily Paavola and Linsey Vann, A Jury of Your Peers? Not Always in South Carolina (2016)

Civil versus criminal

In a criminal case, a government prosecutes a defendant for committing a criminal act.

In a civil case, a plaintiff sues a defendant for violating a private right.

"Civil"

As you know, civil law is broader than just tort law. And "civil law" also has a different meaning that's especially important in Louisiana, Quebec, and countries outside the former British Commonwealth. If you're interested, it's a great question for office hours!

We'll see similar linguistic issues arise repeatedly during the semester: Seemingly simple words often have multiple meanings that may diverge, overlap, and differ from common understandings. Pay attention to this as you read and write throughout your career.

In fact, you might even consider starting a list now. If you do, here's another important term to add: "holding." We'll discuss it soon.

Evidence

Satisfying the burden of proof requires evidence. Consider these model jury instructions:

Evidence can come in many forms. It can be testimony about what someone saw or heard or smelled. It can be an exhibit admitted into evidence. It can be someone’s opinion.

Direct evidence can prove a fact by itself. For example, if a witness testifies she saw a jet plane flying across the sky, that testimony is direct evidence that a plane flew across the sky.

Some evidence proves a fact indirectly. For example, a witness testifies that he saw only the white trail that jet planes often leave. This indirect evidence is sometimes referred to as 'circumstantial evidence.' In either instance, the witness's testimony is evidence that a jet plane flew across the sky.

As far as the law is concerned, it makes no difference whether evidence is direct or indirect. You may choose to believe or disbelieve either kind. Whether it is direct or indirect, you should give every piece of evidence whatever weight you think it deserves.

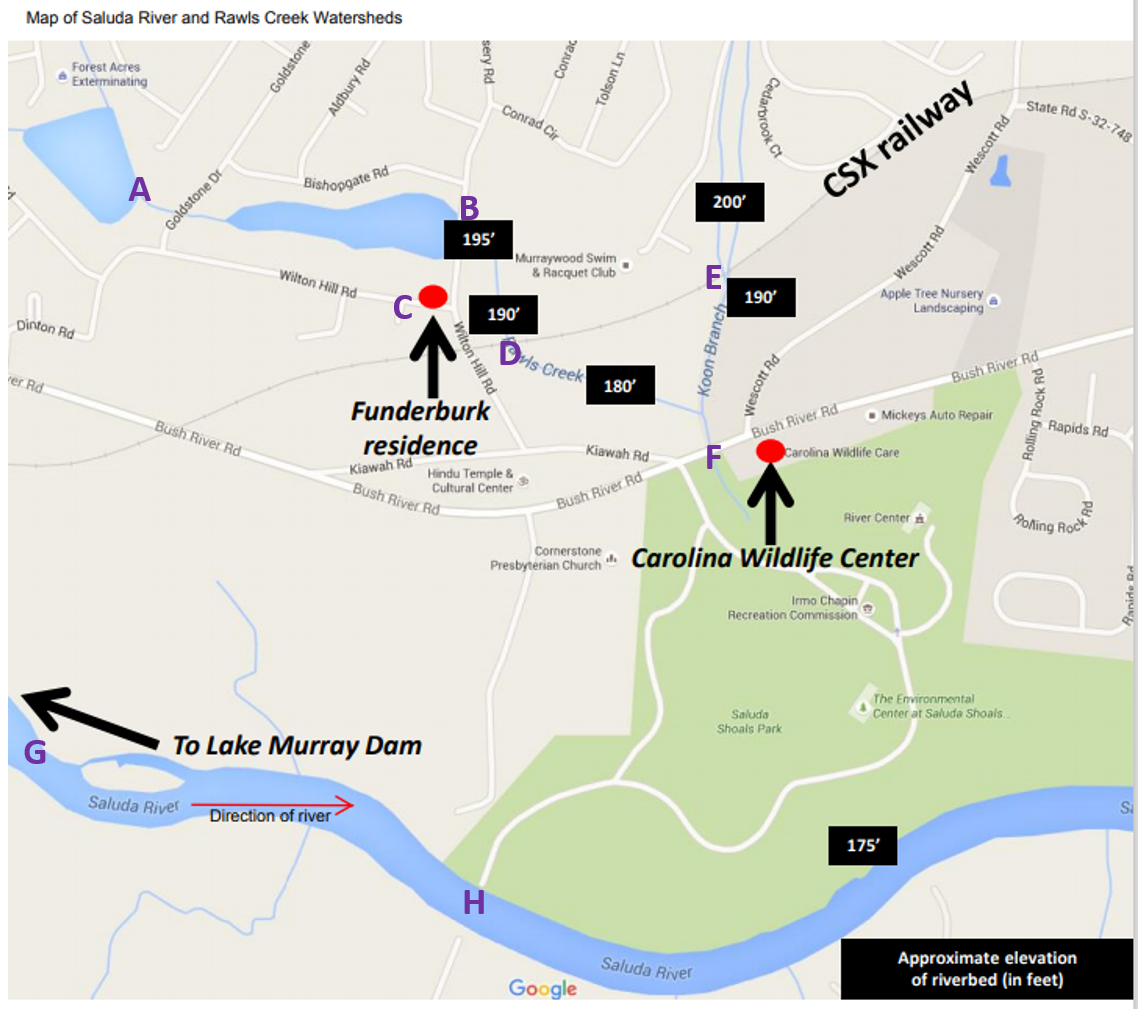

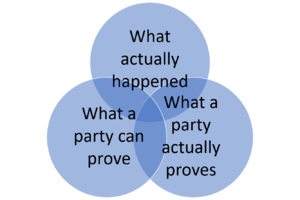

The "facts" in a courtroom can differ from the "facts" on the ground:

Why might this be?

Venn diagrams

We will be using many stylized Venn and Euler Diagrams!

Facts versus law

Other standards

We've already discussed standards of proof. Soon we will also discuss other important standards at the trial and appellate levels. Consider, for example:

- What standard should a trial court apply when deciding whether to grant a motion for summary judgment?

- What standard should an appellate court apply when deciding whether to affirm or reverse a trial court's decision to grant that motion?

(This is the end of the notes for the current class.)

Testing your briefing

Except where you are told otherwise, answer these questions by referring only to your brief -- not to the case itself.

Levels of culpability

Theories of liability

Elements of negligence

Much of this course focuses on "the five elements of the prima facie case of negligence plus the affirmative defenses." These five elements of the prima facie case of negligence are:

- Duty: Whether tort law imposes a standard of care on this kind of defendant in this kind of case.

- Breach: Whether the defendant's conduct fell below that standard of care.

- Factual Cause: Whether the defendant's breach contributed to the plaintiff's harm.

- Scope of Liability: Whether the defendant should be held liable under the specific circumstances of this particular case.

- Damages: Whether the plaintiff suffered a harm for which tort law provides a remedy.

The plaintiff must prove the prima facie case. This means that the plaintiff has the burden of pleading each element, the burden of producing evidence about each element, and the burden of persuading the judge or jury that this evidence satisfies the standard of proof for each element. (Recall: What is the most common standard of proof in tort law?) Imagine the plaintiff trying to roll a boulder up a hill.

Whereas the element of duty is a question of law that is (mostly) decided by the judge, the remaining elements are questions of fact that are (mostly) decided by the finder of fact. (Recall: Who is the finder of fact in a jury trial? Who is the finder of fact in a bench trial?) We will soon talk more about what "mostly" means.

The defendant can offer evidence and arguments for why the plaintiff's prima facie case should fail. Remember: The plaintiff has the burden of proof on the prima facie case, which means that the defendant's evidence and arguments can make it more difficult for the plaintiff to carry that burden. (If the plaintiff is trying to roll a boulder up a hill, what is the defendant doing?)

In addition, the defendant can raise one or more "affirmative defenses" that apply even if the plaintiff proves the prima facie case. In contrast to the prima facie case, the defendant must plead and prove an affirmative defense. This is why it is called an "affirmative" defense. (Now who is trying to roll the boulder up the other side of that hill?) In effect, the defendant argues that even if the elements of negligence are satisfied, there is some other reason why the plaintiff should recover either no damages or less than their full damages.

You have already seen an example of this. Stop and think! What was the defendant's argument in Baltimore & O.R. Co. v. Goodman, 275 U.S. 66 (1927)? Stop and think! This affirmative defense was called "contributory negligence": The plaintiff should recover nothing because their own unreasonable conduct was a cause of their harm. Was it successful? Stop and think!

Early in the semester, many students confuse the element of breach in the prima facie case with an affirmative defense such as contributory negligence or (as we will see) comparative fault. Don't make this mistake! The element of breach is about the defendant's conduct, not the plaintiff's! The reasonableness of the plaintiff's conduct might have nothing to do with the reasonableness of the defendant's conduct. (Like most things, we will complicate this slightly over the course of the semester.)

This brings us to another crucial point: Reality is messier than theory.

In our course, you will see how the substance of tort law varies both across time and across space: Different jurisdictions (and even different judges in the same jurisdiction) do different things at different times. Each state has its own common law, and that common law changes both subtly and dramatically over time. Some jurisdictions still follow legal rules that other jurisdictions abandoned half a century ago. And some jurisdictions have even returned to rules that they once abandoned.

You will also see how the language of tort law varies both across time and across space: Different jurisdictions (and even different judges in the same jurisdiction) say the same things in different ways or say different things in the same ways. For example, later this semester we will see how different courts might frame the very same issue as one of duty or of breach or of scope of liability or of assumption of risk (another affirmative defense). This framing can even affect the outcome: Substance and language are in many ways inextricably intertwined.

Consider one final -- and very important -- example: As you will see in our upcoming cases, many courts still refer to "proximate cause" as one of the elements of negligence. Some use this term to refer only to the element of factual cause, some use it to refer only to the element of scope of liability, and some use it to refer to the combination of these two elements. Because I find this term confusing, I do not use it in our course. Should you? Stop and think!

The answer has little to do with whether this term is actually confusing, whether you find it confusing, or even whether I find it confusing. Rather, the answer has everything to do with an essential legal skill: Knowing your audience. For the purpose of your grade in this course, I am your audience. It is a jurisdiction of one. You (usually) should not use this term in this course because I (usually) do not want to hear it in this course.

After you finish this course, however, your audience is unlikely to be (only) me. How will your answer change if, in the future, you are taking a bar exam that still uses the term? If you are working for a lawyer or arguing before a judge who prefers it? If you are talking with a client who doesn't understand it?

That last one is a trick question. Over the next few weeks, you are going to learn a ton of legal substance and legal language. You will probably vomit your new legal vocabulary in ways that, in retrospect, will be hilarious. And then you will get gradually more competent and correspondingly more confident. Keep your competence and confidence aligned! And never forget what it feels like now. Your ability to talk clearly, simply, and relatably with clients, witnesses, and jurors -- often without legal terms of art -- will be one of your greatest strengths as a lawyer.

Whenever you encounter a new term of art, note it, define it, and make sure that you can use it correctly -- but also make sure that you can explain the same concept without it. This is great practice -- with your friends, family, pets, and blank walls. And it's even appeared on at least one of my past exams.

So what are the elements of the prima facie case of negligence?

Drafting a complaint

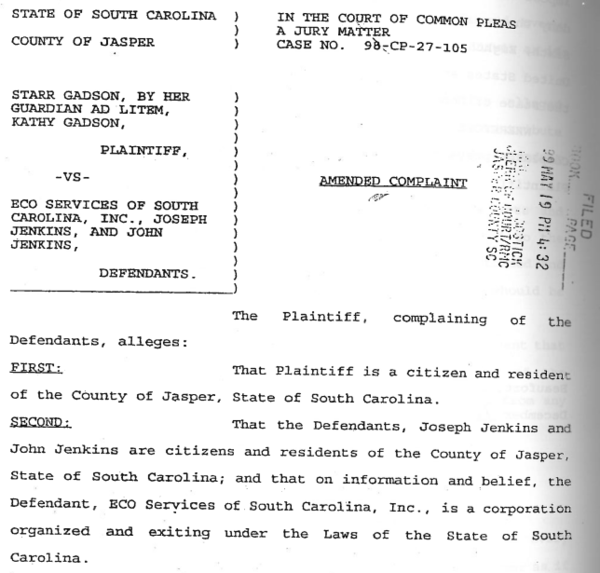

You have already read about the "complaint" -- one of the key documents with which a plaintiff starts a lawsuit.

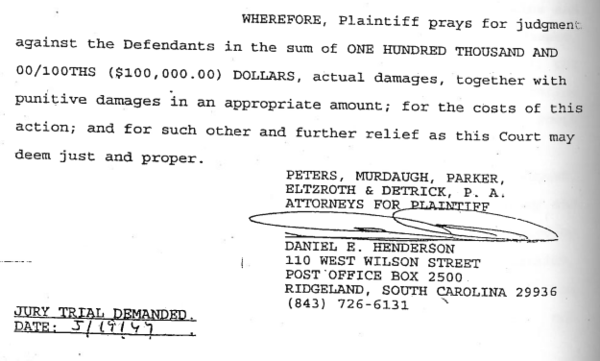

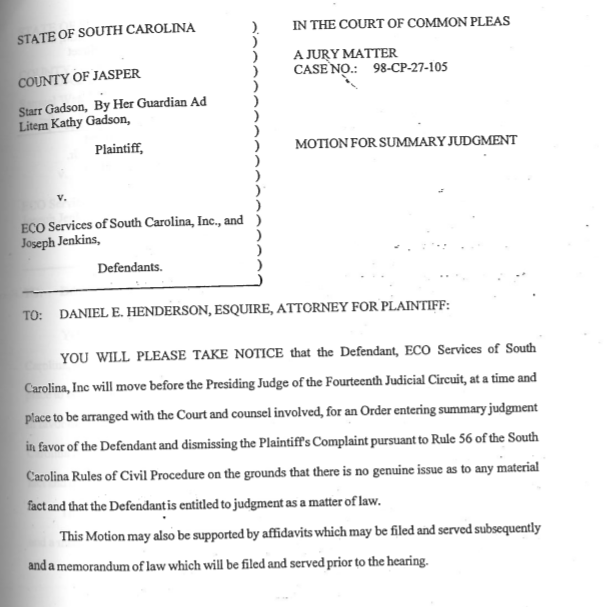

This is the beginning of the complaint in Gadson v. ECO Services:

And this is the end of that complaint:

Your task is to draft the middle of the complaint. It should be clear, concise, organized, and accurate. One careful page is likely to suffice.

The following questions may help you to think through the structure and content of your complaint:

- What are the key facts?

- Who are the defendants? (There are three!)

- What are the claims against each defendant?

- What are the elements of each claim?

- How do the facts relate to each element?

The court discusses negligent entrustment at length -- and soon we will too. For this exercise, however, I suggest you draft your complaint to allege only a claim of negligence generally against each of the three defendants (for a total of three claims).

You are welcome to work alone or with others to draft your complaint. Regardless, you must print and bring your own individual hardcopy.

Model complaint

Do not read this until after class.

Note 1: This is a stylized model for the substantive portions of Starr Gadson's complaint. You will learn about the specific requirements for complaints next semester.

Note 2: It is also acceptable to use the elements of negligent entrustment in addition to or instead of the elements of negligence for claims against ECO and Joseph Jenkins.

Facts

- ECO Services made its truck available to its employee, Joseph Jenkins.

- Joseph allowed John to drive the truck.

- John drove the truck dangerously.

- This dangerous driving resulted in a crash.

- Starr sustained serious physical and emotional injuries because of the crash.

Claim of negligence against John Jenkins

- Duty: John had a duty to exercise reasonable care while driving.

- Breach: John drove dangerously.

- Cause-in-fact: John's dangerous driving caused the crash that injured Starr.

- Scope of liability: It was foreseeable that John's dangerous driving would injure Starr.

- Damages: Starr suffered serious physical and emotional injuries.

Claim[s] of negligence [and negligent entrustment] against Joe Jenkins

- Duty: Joseph had a duty to exercise reasonable care in loaning the truck.

- Breach: Joseph loaned his truck to a dangerous driver.

- Cause-in-fact: Joseph's decision to loan his truck enabled John's dangerous operation of that truck and, ultimately, the crash that injured Starr.

- Scope of liability: It was foreseeable that loaning a truck to a dangerous driver could result in a serious crash.

- Damages: Starr suffered serious physical and emotional injuries.

Claim[s] of negligence [and negligent entrustment] against ECO

- Duty: ECO had a duty to exercise reasonable care in making its truck available to its employees.

- Breach: ECO made its truck available to a person, Joseph, who should not have been trusted.

- Cause-in-fact: ECO's decision to make its truck available to Joseph enabled Joseph to loan the truck to John, which enabled John's dangerous operation of that truck and, ultimately, the crash that injured Starr.

- Scope of liability: It was foreseeable that loaning a truck to someone who was not trustworthy could result in a serious crash.

- Damages: Starr suffered serious physical and emotional injuries.

Summary judgment in Gadson

ECO Services actually moved for summary judgment prior to trial:

- Should the trial court have granted summary judgment in favor of ECO?

- Had Joseph Jenkins moved for summary judgment, should the trial court have granted his motion?

- Had John Jenkins moved for summary judgment, should the court have granted his motion?

- Conversely, had Gadson moved for summary judgment against John, should the court have granted her motion?

Gadson questions

Vicarious liability

Instructions: Lawyers must be careful readers. Important information will often be buried deep within dry prose -- sometimes unintentionally and sometimes deliberately. An entire section's meaning can be changed, or its significance negated, by a phrase hidden deep within a long paragraph that appears thousands of words away in the same text or perhaps even in another text. For example, later in this assignment, you will be told to read a lengthy encyclopedia article about a foreign country's labor law. In fact, that article is not part of this assignment, you do not need to read it, and I will not test you on its contents. It is at best marginally relevant to our course (although, in law, everything is potentially relevant). Because you are reading this paragraph, you will instead be able to spend your time on what actually matters for this course. Some of your colleagues may unfortunately learn this lesson the hard way, but it is an important lesson that they need to learn sooner rather than later. For that reason, please discuss these instructions with them only after our next class.

- Labour law: Carefully read this article in its entirety. Ask yourself: How is this relevant to what we have just studied? You will be tested on this at some point this week.

- Law school fundraising: Janice, a law student, volunteers to ask alumni of her school for donations to a new scholarship fund. The school gives her a list of 100 alumni, a prepared script, and instructions to call them sometime between 6pm and 8pm on weeknights over the next month. When she asks about long-distance calls, she is told she can use a phone at the school. Janice drives to the beach early the next morning. On the way, she pulls out her cell phone to call the first person on the fundraising list. While looking down at the script, she fails to notice that the car in front of her has suddenly slowed. She rear ends that car, injuring its occupant Darla. As the school’s lawyer, discuss.

- "Discuss"

- "Discuss" is a common law school exam prompt. It requires you to identify, prioritize, and organize issues. What you answer and how you answer are closely related, and both will affect your grade.

- "Discuss" is not the only possible exam prompt. For example, you may instead be directed to analyze only certain issues, to advocate a particular position, or to advise a client. Different prompts require different answers.

- Always read (and reread) the prompt -- before you read the question, again after you read the question, again as you are outlining, and again when you finish writing.

- In this hypo, the full prompt actually reads, "As the school's lawyer, discuss." This is an important qualification. It means that you are to write from the perspective of the school's lawyer. It does not mean that you are to necessarily conclude that the school has no liability -- or to dismiss or ignore arguments for why the school might be liable. Quite the contrary: Effective representation requires candor. If your client has liability exposure, it needs to know.

- How would you approach this question differently if the prompt instead read, "As the school's lawyer, what arguments might you use in settlement negotiations with Darla"? For both ethical and strategic reasons, you still should not ignore arguments that may not favor your client. Why not?

- Your writing assignment

- Answer this law school fundraising hypothetical as though it were an exam question. You do not need to do any new research, but you do need to reference the law that we have already learned. You may discuss this hypo with your classmates only after you have fully answered it by yourself.

- While you should identify the important predicate issue in this hypo, you don't yet need to analyze it. But here's a hint about that predicate: For what might the school be vicariously liable? This is the topic that will be the focus of most of our semester!

- Remember: Run toward, rather than away, from uncertainty. Areas of factual and legal ambiguity and inconsistency are where you can do some of your best analysis!

- After you complete this writing assignment:

- Read Restatement (Third) of Agency §§ 2.04 & 7.07.

- So far you have read sections from the most recent version of the restatement for the law of torts. There are also a series of restatements for the law of agency.

- Read both the rule and the comment for Restatement (Third) of Agency § 2.04 and at least the rule for Restatement (Third) of Agency § 7.07. (You might also find comment b helpful.)

- Read Restatement (Third) of Torts: Phys. & Emot. Harm § 57 (2010).

- You need read only the rule itself.

- What are the exceptions? (In law, definitions and cross-references are essential reading.)

- Review the model answer:

- Read Restatement (Third) of Agency §§ 2.04 & 7.07.

Darla might bring (1) a vicarious liability claim against the school for Janice’s potential negligence and (2) a negligence claim against the school for its training and supervision of Janice. In short: While it is not clear that Darla would win, these claims might have merit and so I recommend that the school negotiate with a view toward settling.

1) Darla’s claim of vicarious liability against the school for Janice’s alleged negligence

To recover under vicarious liability, Darla would need to show that (a) she has a claim of negligence against Janice, (b) Janice was an “employee” of the school, and (c) Janice’s negligence occurred within the scope of that employment.

1a) Was Janice negligent?

The given facts strongly suggest that Janice was negligent: Janice has a duty to exercise reasonable care while driving; she breached this duty by looking at her cell phone while driving; this breach might have been a cause-in-fact of the crash that injured Darla (although we would need more facts); this is within the scope of liability because a crash is a foreseeable result of distracted driving; and Darla likely suffered some physical harm (in addition to the damage to her vehicle). [Note: You will learn all this.]

1b) Was Janice an employee?

A third-party tortfeasor can be considered an “employee” for the purpose of vicarious liability even if they are not formally employed by the defendant. In this case, Janice was a volunteer.

[If you actually know this legal rule:] A volunteer can be considered an employee. [Otherwise:] While I do not know of a specific rule, there may be compelling public policy reasons for treating a volunteer as an employee: An organization that relies on volunteers acts through those volunteers in the same way that a company that relies on employees acts through those employees; the injuries caused both by volunteers and employees are costs of doing business; and an organization is in a better position to compensate (and insure) than an individual. Nonetheless, we might argue that organizations that rely on volunteers already receive special treatment under the law and should in this regard as well.

Assuming that a volunteer can be considered an employee, the key issue is whether Janice herself would be considered an employee. Per Uber v. Doe, the most important factor is the right of control. Here, Darla would point to the instructions and particularly the script that the law school gave Janice. We would point to the flexibility that the school provided in where, how, and perhaps even whether Janice made the calls.

Other factors might also be relevant (as in Doe). Carla could argue that Janice’s fundraising calls are not a distinct business, are generally supervised, do not require much skill, used or could have used some school resources (like a phone), and are part of the school’s core work. We might respond that Janice supplied most of her equipment, provided her services for a short period, and received no payment. Under these ambiguous circumstances, the factfinder would likely decide this factual issue.

1c) Was Janice acting within the scope of employment?

Assuming that Janice is an employee, Darla would next argue that Janice’s distracted driving occurred in the scope of her employment. Janice’s multitasking makes this confusing, because her potential negligence involved two simultaneous elements: using her phone (which on its own would likely fall within the scope of employment) and driving (which on its own would likely fall outside the scope of employment). Darla would emphasize both the calling and its benefit to the school to place this within the scope, while we might emphasize the driving to place it outside the scope. We could further argue that, by driving to the beach, Darla was engaged in an unrelated frolic rather than a mere detour.

While we could make our arguments in good faith, Darla’s arguments seem more likely to convince the judge or jury deciding this factual question—and maybe even a judge deciding this as a matter of law. Because of the rise in telework and multitasking, courts (and insurers) may want to clarify this rule more generally (as in Goodman).

2) Darla’s claim negligence against the school for its training and supervision of Janice

Darla might also bring a claim of negligence against the school related to its training or supervision of Janice [but we have not yet discussed negligence at length so the analysis is not included here].

This completes the final class of our Torts introduction! Before we turn to negligence, you should organize and reflect on our material to date.

Making sense of duty

We've already discussed how good lawyers can make order out of chaos. With that in mind: Welcome to some doctrinal chaos! Duty is an amorphous concept that has evolved both in its function and in its content, that still means very different things in different jurisdictions, and that somehow manages to spill over into most of the other elements of negligence (and even into the affirmative defenses).

As you read our duty materials, try to make sense out of them for yourself. Experiment with checklists, flowcharts, and tables. And pay close attention to these six overarching themes:

- Default Duty. What is the default rule for duty? If the default is a "general duty of reasonable care," then most of the specific rules that we will study represent "duty limitations." But if the default is "no duty," then most of the specific rules that we will study represent "limited duties."

- Feasance. The distinction between action and inaction is much more important for the element of duty than for the element of breach. Why might this be?

- Foreseeability. Duty might be a function of foreseeability. What was foreseeable in MacPherson? Look for the role that foreseeability plays throughout our duty materials -- and, indeed, throughout our entire course. Does foreseeability still belong in duty? What does the Restatement (Third) say?

- Relationships. Duty might also be a function of relation. What was the special relationship in MacPherson? Look for the role that special relationships play throughout our duty materials.

- Standards of Care. Which of our so-called duty rules are about the nature rather than the existence of a standard of care? We can think of some duty rules as setting a standard other than "reasonable care." Alternately, we can think of these rules as effectively defining what constitutes "reasonable care" in certain kinds of situations. Although we are focusing on negligence, you should also consider how you would formulate a duty rule for strict liability.

- Damages. Which of our so-called duty rules are actually rules about damages? When might "the defendant has no duty" really mean "the plaintiff has not suffered the kind of damages for which tort law provides a remedy"?

You can find at least one of these themes in each of the cases that you will read and in each of the rules that you will learn.

I encourage you to work with your CCC team to track these themes (and any others) throughout our duty section.

Breach versus comparative fault

Hazing hypo

Fraternity A at public university B organizes an event to induct its new members. B has a written policy that prohibits “hazing in all forms.” This policy has been adopted by regents appointed by the state’s governor.

A recent TikTok craze has inspired many fraternities across the United States to transform their houses into obstacle courses for their induction ceremonies. A is no exception: It is eager for its new and established members to bond by completing an intense physical challenge.

C, an alumnus of A who works as a construction engineer, designed and built A’s massive obstacle course. As a volunteer liaison for A’s national organization D, C also regularly reports back to D on activities, issues, and concerns at A, pursuant to detailed instructions from D.

On the night of A’s induction ceremony, the members order pizzas from E. F is a 16-year-old employee of E who works primarily for tips. She delivers the pizzas to A. At the door, the members of A invite F in while they collect the cash to pay her. When F notices the obstacle course, one of the members offers F a 50% tip for successfully completing the course.

As F scrambles up a two-story ladder built by C as part of the obstacle course, inebriated members of A begin throwing pizza slices at each other. (Some of A’s members are present. Of those present, some are inebriated and some are throwing pizza slices.) The pizza grease makes the ladder rungs, which C polished perfectly smooth to avoid splinters, even more slippery.

Believing she is about to fall, F jumps and lands on G, a 20-year-old inductee. They are both injured. In the ensuing panic, a lamp is launched through the window, sending shards of glass into the eyes of passerby H.

Everyone present at the induction ceremony has only a very hazy recollection of the night’s events.

But-for test

Answer these questions according to the pure "but for" test described by the Caruso court.

Substantial factor test

You have now encountered the two principal tests for the element of factual cause (also known as cause-in-fact): the "but for test" and the "substantial factor test." Based on their descriptions in Caruso and Clark, how do you think they compare?

In theory, there are some instances where the pure but-for test would produce a different outcome than the substantial factor test. (You've already seen one such example in the "but-for" quiz above.)

In practice, however, both approaches generally produce the same result. Some jurisdictions use a but-for test but address these edge cases through either an express allowance (per the Restatement (Third)) or the substantial factor test. Other jurisdictions use a substantial factor test that generally incorporates the but-for test (per the Restatement (Second)).

The essence of the element of factual cause is that the defendant's breach contributed to the plaintiff's harm. Start and end with this basic inquiry -- and don't lose sight of it as you are considering whether and how to apply the but-for and substantial factor tests.

Language

Our third element in the prima facie case of negligence ("factual cause" or "cause-in-fact") is where the language of torts really starts to go off the rails before crashing spectacularly in our fourth element ("scope of liability").

Various courts variously use various terms such as "proximate cause" and "legal cause" to variously refer to the element of factual cause alone, to the element of scope of liability alone, or to the combination of factual cause and scope of liability. (This is kind of like saying that "apple" and "orange" might mean "apple" or "orange" or "apple-orange.")

Although I will generally use the language of the Restatement (Third) of Torts ("factual cause" and "scope of liability"), you will see that many court opinions do not. Whenever you encounter terms like "proximate cause" and "legal cause," try to figure out what the court really means.

More factual cause

Reading Thomas

The lengthy case that follows illustrates how complex, creative, and contentious tort law can be. The case is a shorter read than it may seem at first.

The first hundred paragraphs of the majority opinion consist largely of a recitation of facts that you should read attentively but that you need not analyze closely.

The key legal portion of the majority opinion discusses Wisconsin’s distinctive “risk-contribution” theory of liability. Corresponding portions of the two dissents disagree with the majority’s application of this theory to the facts of this case. Another part of the majority opinion (along with much of the first dissent) involves an issue of state constitutional law; you can lightly read these portions for their style rather than for their substance.

You may use this narrative guide to further ease your reading. Reviewing this guide before the case may help you focus on the key parts; reviewing this guide after the case may help you check the effectiveness of your reading strategy. The choice is yours.

¶¶ 1-4

It’s nice of the court to give us a roadmap, but I wish they didn’t plop us down right in the middle of the freeway. Grab ahold and hang on.

The plaintiff (Thomas) is trying to recover from several lead pigment manufacturers (the defendants) for lead-related injuries under three theories: “risk-contribution” (per Collins v. Eli Lilly Co.), civil conspiracy, and enterprise liability.

Because this case is an appeal of summary judgment for defendants, the Wisconsin Supreme Court is deciding whether Thomas will get a chance to prove his case.

The court thinks that the “risk-contribution theory” applies (whatever it is) but that the plaintiff’s two other theories are not viable.

¶¶ 4-25

The court is necessarily construing the facts in the light most favorable to the plaintiff. The plaintiff is suffering permanent cognitive impairment and other potentially severe health risks from ingesting lead paint in his childhood homes. He has had limited success in recovering from the owners of these homes. Because these are old homes with many layers of lead paint, there is no way for the plaintiff to determine which companies actually manufactured the lead pigment that was used in that paint—but he can show that the defendants manufactured that kind of lead pigment (white lead carbonate) during the relevant period. The lower courts did not think highly of the plaintiff’s claims for reasons that would make much more sense if we knew what the “risk-contribution theory” was.

¶ 26

This is just the standard for deciding summary judgment. We know this!

¶¶ 27-28

Nobody in the plaintiff’s position could possibly ever trace the specific paint chips they ingested back to individual manufacturers. Does that mean that these injured plaintiffs cannot recover from negligent manufacturers? Some courts think so—but there must be a better way.

¶¶ 29-35

Lead is really, really, really bad. [We’ll talk more about this in class, but it’s worth taking the time to appreciate how bad. Lead—in paint, fuel, pipes, and other materials—is one of the biggest health catastrophes in American history. It remains a major threat to public health and to socioeconomic justice.]

¶¶ 36-40

Although there are some differences among the various forms of white lead carbonate used in lead paint, they are all equally dangerous.

¶¶ 41-98

Pigment manufacturers have known since at least the early 1900s that lead paint is incredibly toxic, particularly for children, and that far safer alternatives exist—and yet they actively sought to promote lead paint, conceal its dangers, and avoid regulation. [The reprehensible conduct of the lead industry is also worth taking the time to appreciate. They rank close to the tobacco industry.]

¶¶ 99-109

Now we’re finally going to learn about the risk-contribution theory, courtesy of Collins v. Eli Lilly Co. From 1938 to 1971, doctors commonly prescribed a synthetic estrogen called DES to pregnant women to prevent them from miscarrying. Many of the children of these women eventually developed severe health problems, including cancer and infertility. The plaintiff in Collins was one of these offspring.

Like her many counterparts, there was no way that the plaintiff could identify which of the numerous DES manufacturers had produced the specific DES pills prescribed to her mother decades earlier. And so, even if she could show that every DES manufacturer had breached its duty, she could not causally link a particular manufacturer’s breach to her injuries.

[In the landmark case of Sindell v. Abbott Laboratories, 26 Cal. 3d 588 (1980), the California Supreme Court addressed this problem by recognizing a theory of “market share liability” for products that are both defective and fungible. Under this theory (which built on Summers v. Tice), a plaintiff who sues the manufacturers that represent a substantial share of the product’s market must still prove individual breach but can prove collective causation. If successful, the plaintiff can then recover from each manufacturer for the share of her damages that corresponds to its share of the relevant market.]

In Collins, the Wisconsin Supreme Court recognized a similar “risk-contribution theory” that allowed a plaintiff to recover from manufacturers that had contributed to the total risk by "produc[ing] or market[ing] the type of DES taken by the plaintiff's mother." This involves a burden-shifting arrangement and guidance to the jury on assessing this contribution. [Both of these are very important conceptually!]

¶¶ 110-130

[State constitutions can be inspiring, disturbing, important, and interesting.] In Collins, the Wisconsin Supreme Court cited a state constitutional provision that anyone who is injured is entitled to a remedy. The defendants in Thomas try to distinguish their case by arguing that the plaintiff in their case has a remedy (against the landlords). For reasons of fact, law, and policy, the court rejects this argument as a distinction without a difference.

¶¶ 131-136

The court decides that the risk-contribution theory also applies in this case. The plaintiff is severely injured through no fault of his own, whereas the defendants are bad actors in a much better position than the plaintiff to absorb the costs of his injury.

¶¶ 137-149

Furthermore, to the extent that fungibility matters, white lead carbonate is sufficiently fungible.

¶¶ 150-160

The defendants' other arguments against application of the risk-contribution theory are also unpersuasive. The fact that the plaintiff cannot determine what decade the lead paint at issue was applied in fact illustrates “the magnitude of [the defendants’] wrongful conduct.” The fact that cognitive impairment can be caused by factors other than lead poisoning should not affect defendant’s opportunity to prove that his cognitive impairment was caused by lead poisoning. And the fact that the defendants lacked “exclusive control” of their product’s risk does not diminish the defendants’ own deplorable culpability.

¶¶ 161-163

And so we reach the elements for a negligence claim and a strict liability claim based on the risk-contribution theory (including the burden-shifting framework).

¶¶ 164-166

Other arguments offered by the defendants and the dissenters are not ripe or not persuasive.

¶¶ 167-172

Civil conspiracy is another theory of liability. [Note the elements!] But this theory requires more than merely parallel behavior, and the plaintiff has not pled facts sufficient to establish the necessary level of coordination.

¶¶ 173-176

Enterprise liability [as the term is used here] is another theory of liability based on collective conduct by the entire industry, but the plaintiff has not pled facts that suggest such conduct here. [For its other meanings, see Black’s Law Dictionary.]

¶¶ 177-318

Now we turn to the equally lengthy dissents. Together, they make three principal sets of arguments framed, respectively, in terms of law, fact, and policy.

First, the majority is voluntarily expanding the rule from Collins. [Is the expansion of a common law rule necessarily unusual or inappropriate? Note, in this regard, the first dissent’s reference to the modern rule of duty.]

Second, the white lead carbonate industry was much more complex, diverse, and multistreamed than the majority describes. [How would the risk-contribution theory also account for these characteristics?]

Third, the majority’s rule could unfairly impose significant liability on particular companies and industries—and especially Wisconsin companies and industries. [Carefully consider each of the six public policy factors discussed in the second dissent. That dissent also makes several (principally federal) constitutional arguments; you will learn more about procedural due process, substantive due process, and equal protection in constitutional law next semester.]

Story of Palsgraf

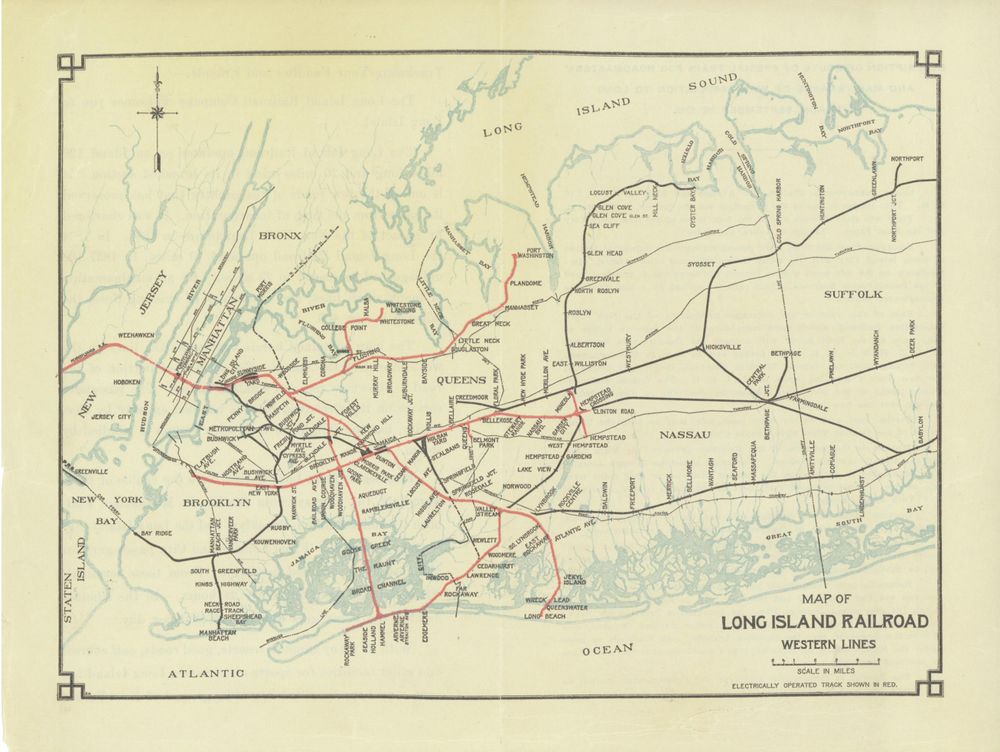

Helen Palsgraf was at the Long Island Railroad's East New York station:

The East New York station is just northeast of the word "BROOKLYN" on this map:

A thoughtful student once pointed out that it would be interesting to know where the parties in our cases are today. I agree.

In some instances, I've been reluctant to intrude into the personal lives of people who were so affected by the real tragedies that we use to learn law. A few years ago, I found what are probably the social media accounts of a teenager who, as an infant, lost their parent in a crash that gave rise to one of our cases. It felt way too voyeuristic.

In many other instances, we really don't know what happened to the people involved.

As perhaps the most famous case in all of law school, Palsgraf v. LIRR is both an exception to and an illustration of this rule. You can learn more about what [we think] we know about the facts of this case in a number of sources, including the book review that follows.

Course philosophy

Torts is the quintessential 1L course.

As you know, tort law itself is an incredibly rich and diverse subject that blends common law and statutory law, doctrine and policy, substance and procedure, and theory and practice. It implicates ubiquitous concepts such as reasonableness, foreseeability, and culpability as well as fundamental questions about law, community, and responsibility. In our world of second-best solutions, it serves both as a backstop and, occasionally, as a leader.

In this course, tort law provides material for learning how to work and think and communicate like a lawyer. Even if you never practice tort law (or law at all), the substance and skills that you learn in this course will resonate throughout your career. This unique opportunity to welcome you to the law is why I choose to teach Torts.

But I cannot, unfortunately, teach all of tort law. There is simply too much. In fact, years ago, Torts was a six-credit, two-semester course. And so I must triage our potential material.

My approach to this triaging, and to teaching generally, is to achieve both depth and breadth. In this course, that means diving deep into the tort of negligence while superficially surveying almost every other tort. Picture a capital "T" with negligence as the vertical and our other torts as the horizontal.

Our depth is important for two reasons. First, negligence is by far the most important tort -- the one you are mostly likely to use in practice (and, for that matter, see on the bar exam). Second, diving deep into the history and diversity and complexity and chaos of just one tort is important for developing a rich understanding of law more generally. You will be able to apply the competence, confidence, humility, and creativity that you have gained by studying negligence to other torts and even to other areas of the law. You will be able to teach yourself.

Our breadth is therefore important because it gives you a place to start. By surveying the other torts, you will create a map for understanding when and where to undertake additional deep dives. You may never in your career encounter, say, the tort of intentional interference with prospective economic relations -- but if you do, you will recognize it and know how to learn more.

This broad map will also help orient you in your future legal work. If you intern at a firm this summer, you can say you're at least familiar with products liability. (And then you can actually take my Products Liability course.) When you take Property next semester, you can say you're at least familiar with nuisance and trespass. And when you're discussing current events with friends and family, you can say -- without giving legal advice -- you're at least familiar with assault, battery, and defamation.

All of this makes for deep depth and broad breadth. Both involve struggling, albeit in different ways. So let me conclude with an imperfect analogy: Just as running makes you faster at running, improves your general wellbeing, and helps you escape a pack of marauding lions, struggling with tort law makes you better at tort law, improves your general legal skills, and helps you tackle your exams.

Keep running!